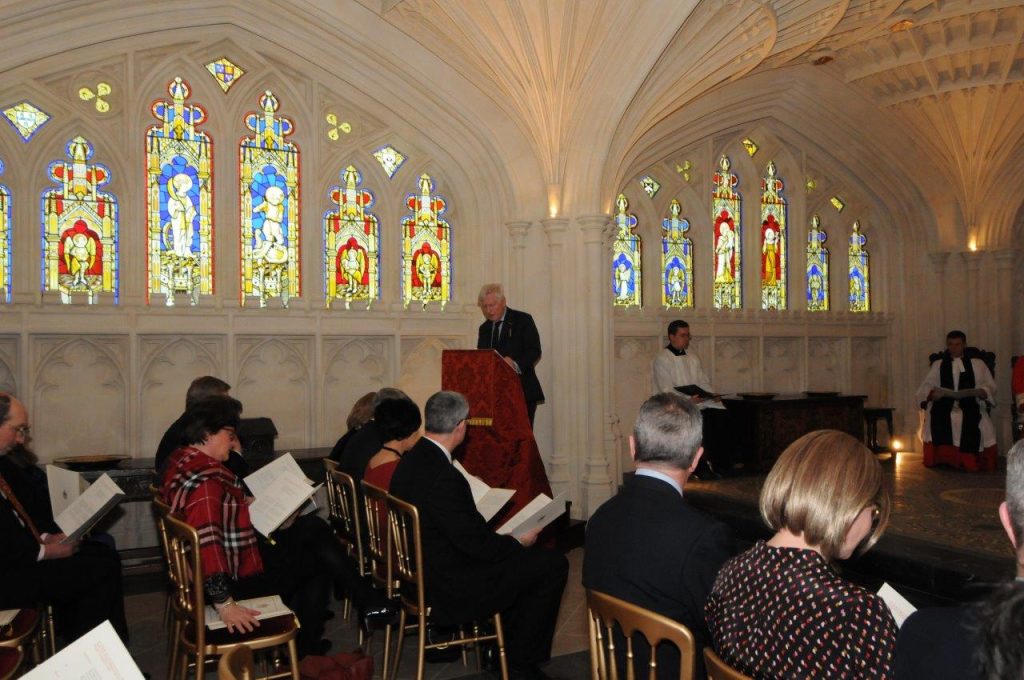

On 20th February 2023, The Chapel of Crosby Moran Hall, built by Dr. Christopher Moran in the undercroft of the 15th Century Great Hall formerly owned by Sir Thomas More, was uniquely blessed in an ecumenical Service of Dedication taken by His Eminence Cardinal Vincent Nichols, Archbishop of Westminster and The Reverend Canon Dr. Jamie Hawkey, Canon Theologian of Westminster Abbey.

The Homily

His Eminence Cardinal Vincent Nichols, Archbishop of Westminster

20 February 2023

The two readings we have just heard, read by Christopher and Emily, speak to us of meeting with God. Jacob’s encounter with the Lord, in a dream, offers him reassurance that God is with him and his descendants, and will never abandon them. The vision of the ladder, reaching from heaven to earth, prompts Jacob’s famous exclamation, that ‘this is nothing less than the house of God, and this is the gate of heaven’ – words that have found their home in many a church and sacred space over the centuries. Indeed, the name Jacob gives to the place of the vision, Bethel, means ‘House of God’.

Jacob’s encounter with God was a solitary one. Nathaniel, of whom we heard in the second reading, was not alone. Jesus was there, and Philip and very probably others too.

Now we know that much prayer is undertaken alone. Jesus himself recommends the practice: ‘when you pray, go to your private room and, when you have shut your door, pray to your Father who is in that secret place’. (Matthew 6:6). But that exhortation was given as a warning against a sort of public prayer that is ostentatious and hypocritical – undertaken to burnish the ego of the individual, not to raise up the mind and heart to God. Christian discipleship is not, and never has been, purely a solitary pursuit. It is personal – a decision for God, a determination for a constant turning towards Christ – but it cannot be individualistic, cut off from our fellow-Christians. The God in whom we believe is himself relational, in the inner life of the Trinity. All praises, then, whether alone or in common, are made in the name of the Father, and the Son, and the Holy Spirit, and in the context of the Church.

St John Henry Newman, who made such a contribution to the life of faith in this country in both his Anglican and Roman Catholic days, wrote an early sermon on the importance of public worship, first preached in 1829. He notes the practice of the early Church in the Acts of the Apostles, as well as the public and ecclesial character of the sacraments. He also observes that ‘Christ has put an especial blessing upon united worship’ and reminds us that ‘It has been the great design of Christ to join all His followers into one, and with a view to this, He has lodged His blessings in the body collectively, to oblige us all to pray together if we wish to gain grace each for himself.’

That is why our churches and cathedrals, our chapels and abbeys, have such significance. They are not mere meeting halls. No. The prayers that are said in them fill their walls, echoing the praises of generations. They are blessed, sanctified, made holy. Many are consecrated some dedicated, an action of the Church that assures us that that, indeed, they are houses of God and gates of heaven. And that is what we do today.

In dedicating this chapel, the figure of another Englishman looms large. In St Thomas More, we see someone who lived out a faith that is not individualistic, and did so with dramatic ramifications. Indeed, if religion had to him been purely a private matter, he might have found it easier to acquiesce to the Act of Supremacy and all its implications. But this he could not do – and that led, in the end, to a stripping away of all that he had, and even to death. We as a nation, and as Christians in this land, have had to live with the consequences of those times, and the divisions they have brought about, for five hundred years and more.

In considering those divisions, we might reflect that Jacob’s encounter with God, in a dream at Bethel, comes about in the context of conflict. He is fleeing from the hatred of his brother Esau, and told by his mother Rebekah to take refuge with her brother Laban in Haran, before Esau can make an attempt on his life. The anger of Esau had been inflamed because Jacob had himself obtained the blessing of his father Isaac in a way that could be described as less than straightforward. Yet out of these murky circumstances came one of the great moments of the Old Testament, one that was alluded to by Jesus himself in his meeting with Nathaniel.

It is a blessing that, today, we can come together, across the denominations and despite the challenges of our history, to worship God in this place, ‘awe-inspiring’ indeed in its beauty and its history. We focus on so much that we have in common, the sure foundation in Christ that is ours, and which our worship in this chapel seeks to express.

In a few moments, we will hear the choir singing one of William Byrd’s great motets, ‘Laudibus in sanctis’. The text is a paraphrase of the last psalm, Psalm 150. Its words speak of the impetus for all creation to give of its best to God in prayer and praise. Voices, trumpets, lyres, timbrels, organs, cymbals. Individually, they might have little impact: the ‘warlike trumpet’ in isolation could even be unsettling, a sound of menace, not of beauty, and far less of praise. But they come together – just as we come together. And in doing so they ‘sing Halleluia to God for evermore.’

That is what we do today, meeting God in this awe-inspiring place. That is what this chapel will do, we pray, long after we who are here today have completed our earthly journeys. For that our hearts are full of gratitude and thanksgiving to God.

Guests and The Moran Family gather for the unique ecumenical Service of Dedication of The Chapel of Crosby Moran Hall taken by His Eminence Cardinal Vincent Nichols, Archbishop of Westminster and The Reverend Canon Dr. Jamie Hawkey, Canon Theologian of Westminster Abbey

After Dinner Speech following the Service of Dedication

His Eminence Cardinal Vincent Nichols, Archbishop of Westminster

20 February 2023

Reverend Fathers, Ladies and Gentlemen,

This evening I start by thanking Christopher and Emily most warmly not only for their kind invitation which brings us together, but more profoundly for creating this unique occasion in such a remarkable and exquisite setting.

So much is said about Crosby Hall, or as I should say, Crosby Moran Hall, that I wish simply to express my constant and unfailing utter admiration for the beauty of this place. Every detail, every facet of the House, Hall and Chapel testify to love and care that is lavished upon this astonishing and unique building.

This evening our focus is on just one of its remarkable owners and inhabitants: Thomas More – Sir Thomas More, St Thomas More – and to reflect on him in the light of the prayer that we have just shared together in his chapel. As we know he served as Lord Chancellor from 1529 to 1532, but already he had served as Secretary and Special Advisor to Henry VIII when, in 1519 he took out a lease on this Crosby Hall, then in Bishopsgate.

I wonder if he knew, in that year, what was about to be unleashed on his world the very next year, 1520? It was then that Martin Luther, following his skirmish about indulgences, published his radical rejections of the Catholic faith, including his book, ‘The Babylonian Captivity of the Church’.

That publication unleashed what can truly be called a state campaign against Luther’s teaching. This included the public burning of his books and the issuing of the King’s own proclamation of Catholic faith, the ‘Assertio Septem Sacramentorum’, published on 12 July 1521. It won for Henry the coveted title ‘Fidei Defensor’, still in use today. Henry had, a few months previously, also ordered the learned men of Oxford and Cambridge to gather together, at his expense, in order to study and refute the attacks of Martin Luther. Sadly the result of many months of study have been largely lost.

I say this to make clear, in case there is any doubt, that Henry was never a Protestant.

Thomas More played his part too. He too issued a refutation of Luther’s work, in 1523, possibly written within this house, and was later involved in the prosecution of those who published and promoted Luther’s teachings. Indeed, much has been written about More’s part in the prosecution – or persecution – of heretics, mostly on the basis of the unproven propaganda of John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. Interestingly, when, in the year 2000, Pope St. John Paul II proclaimed Thomas More to be the patron saint of politicians, he stated that ‘in his actions against heretics, he (More) reflected the limits of the culture of his time.’ I was present in St Peter’s Square for that occasion. I remember it well for I took the opportunity to cross the Square to shake the hand of Mr Gorbachev, also present at that Mass.

But I digress.

Just a few years later, Thomas More became a central figure in the King’s great matter: that of his marriage to Catherine and his determination to marry Anne. Here we come to the break with Rome, through the great acts of Parliament that brought about the imprisonment of More and his execution in 1535, professing to be the King’s good servant, but God’s first.

His execution, and that of the saintly scholar and bishop, John Fisher, sent shock waves throughout Europe. The whole drama that then unfolded over the following century is an enduring part of our shared memory.

But the impact of Luther’s teaching was not to be halted. Rather it found root in this land most quickly in Scotland, through the leadership of John Knox, once a royal chaplain to Edward VI, but then inspired by John Calvin in Geneva. His achievement was the establishing of a Protestant ascendency and polity in Scotland which has endured through the centuries.

These two powerful streams, the emergence of the Church of England with the Monarch as its Head, and the Protestant Reformation, swept through the subsequent decades and centuries, mingling and separating, creating the complex divisions of the Christian life with which we are familiar. They lie behind this evening and the remarkable celebration of a shared faith that we have embraced in this chapel, in the ceremony of its dedication.

This history, and its contemporary setting, were recently addressed directly by our Monarch on a most important but little noticed occasion. On 16 September last year, just three days before his Mother’s funeral, King Charles gathered together the leaders of the different faiths in this country. This is what he said to us:

‘I am a committed Anglican Christian, and at my Coronation I will take an oath relating to the settlement of the Church of England. At my Accession, I have already solemnly given – as has every Sovereign over the last 300 years – an Oath which pledges to maintain and preserve the Protestant faith in Scotland.’

Then he continued:

‘I have always thought of Britain as a ‘community of communities.’ That has led me to understand that the Sovereign has an additional duty – less formally recognised but to be no less diligently discharged. It is the duty to protect the diversity of our country, including by protecting the space for Faith itself and its practise through the religions, cultures, traditions and beliefs to which our hearts and minds direct us as individuals. This diversity is not just enshrined in the laws of our country, it is enjoined by my own faith. As a member of the Church of England, my Christian beliefs have love at their very heart. By my most profound convictions, therefore – as well as by my position as Sovereign – I hold myself bound to respect those who follow other spiritual paths, as well as those who seek to live their lives in accordance with secular ideals. (16 September 2022).’

These words summon from us a response. This evening is one such response, where we who have been divided by history strive to overcome its wounds and walk together in a harmony, and common effort and a sincere dialogue. In other words, to walk in love.

The beautiful service of dedication of the chapel in which together, from our different traditions, we have taken part, brings to my mind many other moments, in recent years, which have also sought to overcome our past divisions and heal their wounds.

For example, I recall with great emotion being in the cell of Thomas More, in the Tower of London, in 2013, with the then Bishop of London, Richard Chartres. We were together in silence, in prayer, in a shared emotion. We pondered on the last days of this great man, in a cold and damp cell, deprived by then of every comfort, books and writing paper included, yet still able to approach death with a peace and serenity which we all admire as a testimony to his integrity and to his faith in the Lord.

And there is one other memory I want to share, to add to the memories that this evening will long evoke.

On 9 February 2016, again at the invitation of Bishop Chartres, I found myself, in full episcopal rig, about to enter the Chapel of Hampton Court Palace.

As we waited, I thought about all the people who, over the centuries, had entered through this same doorway into the Chapel. There were many who preceded the turmoil of the Reformation, including, of course, Cardinal Wolsey. Catherine of Aragon and other wives of Henry VIII prayed there as did Cardinal Pole, at the time of Queen Mary. But it was then my turn. The weight of history was vivid and heavy.

I thought of Henry’s angst and anger at Rome. Earlier I had walked along the Haunted Corridor, past the painting of the four evangelists hurling great stones down onto the figure of the prostrate Pope. It was painted in 1540 and replicated the cover of the first editions of the Coverdale Bible. It is unambiguous.

Yet I also thought about other figures who had entered that chapel for whom life was more ambivalent. I thought of two musicians, Thomas Tallis and the remarkable William Byrd. Elizabeth I wanted him there. She even helped to pay his recusancy fine, which without her help would have been crippling! Her personal desire was for a rich and full liturgy, and she resisted the Puritan pressures of the time. But she also used him, and the chapel, as a significant factor in her foreign policy, bringing ambassadors to its liturgies so that they might send favourable reports back to the Catholic monarchs of Europe.

How fitting that we have again used his music in our prayer this evening. I wonder how many of such people across the centuries, have stepped into the chapel here, the one we have entered together to share our prayer and our hope.

And it is to prayer that we must return, constantly, if those hopes are to flourish. Let us pray constantly that as we continue to shift through the long-lasting aftermath of the events which we recall, we can find those golden threads of profound faith which, if we are humble and receptive, can be woven afresh by the Lord into the banner of Christ’s Gospel to be carried with confidence and joy in our society today.

Ladies and gentlemen, Christopher, thank you for a wonderful evening.

Religious Media:

Photo story: Ecumenical space (churchtimes.co.uk)

https://www.churchtimes.co.uk/articles/2023/3-march/news/uk/photo-story-ecumenical-space

Music of Capella Moreana, directed by Daniel Turner

Ubi Caritas

Antiphon for Maundy Thursday (Traditional plainchant)

Come Holy Ghost

Possibly by the 9th century German Monk Rabanus Maurus (Gregorian Chant)

Libera nos, salva nos

An Antiphon to the Most Holy and Indivisible Trinity (John Shepherd (c. 1515-1558))

Salavtor Mundi

An Antiphon for Matins on the feast of The Exaltation of the Holy Cross (Thomas Tallis (c. 1505 – 1585))

Gloria in Excelsis

From the Ordinary of the Mass (William Byrd (c. 1540 – 1623))

Prevent us O Lord

The Book of Common Prayer (William Byrd)

Laudibus in Sanctis Dominum

A Paraphrase of Psalm 150 (William Byrd)

Sing Joyfully

Psalm 81: verses 1-4 (William Byrd)

Instrumental

Courtly Masquing Ayres, no.1 – John Adson

The Kyngs’s Pavyn – Anon

En vray amoure à 4 – King Henry VIII

In Nomine à 5 – Robert White

Courtly Masquing Ayres, no.20 – John Adson

Bruder Conrads Tantzmass – Moritz von Hessen Kassel

Fanfares – Aria per il Baelletto à Cavallo, Gioanne Enrico Schmelzer & Sonata 336, Cesare Bendinelli

Almaine, no.57 – Antony Holborne

And I were a maiden à 5 – King Henry VIII

Grayes Inne, The First – John Coprario

Greensleeves – Anon

Courtly Masquing Aryes, no.21 – John Adson

Musicians

Daniel Turner (Director), Miranda Heldt, Eloise Irving, Clover Willis, Anna Semple, Daniel Gethin, David De Winter, William Balkwill, Christian Goursaud, John Evanson, The English Cornett and Sackbutt Ensemble: Adrian France, Gawain Glenton, Conor Hastings, Emily White, Tom Lees, Gabriella Jones (Harpist), Augustin Irving (Lutenist)