This week marked the anniversary of the second IRA ceasefire in 1997, and it’s worth recalling for two reasons. The first is self-evident – there was a previous ceasefire which broke down with tragic results for the people of London in 1996.

That was quite personal to me as much of my professional life was spent in the city of London. We had hoped the worst years were behind us. In 1997 neither Anglo-Irish relations or Co-operation Ireland, the leading peace-building organisation which I now lead, were on my radar.

That said, as a businessman with global interests I understood only too well the need for political stability, and the economic consequences of not having it, too.

The process back then was very fragile and both the British and Irish governments were making every effort to create a framework for getting talks started.

Such was the mistrust between the political parties that the task seemed almost impossible. And yet somehow a breakthrough was made. It wasn’t instantaneous nor was it smooth. John Major deserves considerable credit for the risks he took with a Government majority that was equally fragile and against a backdrop of the risk of another failed ceasefire.

The new Labour Prime Minister, Tony Blair, was equally committed along with his Irish counterpart, Taoiseach Bertie Ahern, and both men took active responsibility for the process.

If the scenario seems familiar, it’s because 2017 has some similarities.

And that’s the second reason for marking the second ceasefire. Mistrust has crept back into the peace process, and it is very much a process, because in a contested and sometimes conflicted society like Northern Ireland, peace-building is a journey which requires constant vigilance.

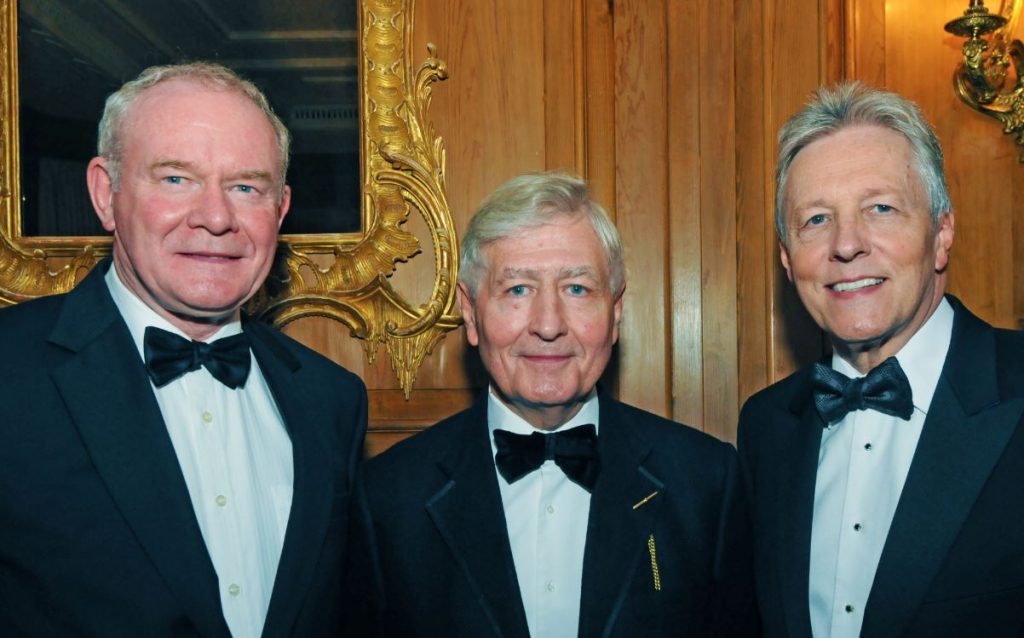

The late Martin McGuinness of Sinn Fein knew that, as did the former leader of the DUP, Peter Robinson, both of whom stepped back from their own natural constituencies to take a look at the wider picture.

Since then, there has been what can only be described as political backsliding. An entrenchment. But there is a way out. Reflecting on the words of former US president Barack Obama, who said, echoing Spinoza, “Peace is not just the absence of war. True peace depends upon creating the opportunity that makes life worth living.

“And to do that we must confront common enemies of human beings: nuclear war, poverty, ignorance and disease.”

In the past year, both the DUP and Sinn Fein have been given strong mandates to return a working administration to Northern Ireland. That provides both leaders, Arlene Foster and Michelle O’ Neill, with huge opportunities to be both brave and bold in a way that would be the envy of other political leaders.

If you take President Obama’s common enemies and translate them into Northern Ireland issues such as combating sectarianism, poor health and inequalities in education – then that becomes a common platform for Arlene Foster and Michelle O’Neill to create the opportunity that makes lives better in Northern Ireland by restoring devolution and impacting on such issues in the interests of all.

While others may be pessimistic, I am actually optimistic that the institutions in Northern Ireland will be restored because both leaders and their parties share in common a deep desire to improve the well-being of the people of Northern Ireland.

It’s what drives both and it’s common ground, rooted in a sense of service to their communities.

It’s something which is also shared by the leaders of the SDLP, UUP and Alliance who, far from being on the sidelines, are important to the cementing of any future administration. Why? Because inclusion works in Northern Ireland.

During this current impasse, it has been disappointing to see some of the unnecessary and often nasty critiquing of those tasked with finding a mutually beneficial solution. I know just how hard all of the political leaders in Northern Ireland work and just how committed they are to achieving a result that will produce something lasting.

It can’t be ignored that Brexit has put strains not only on relationships between the Northern Ireland parties but also between the UK and Ireland. Northern Ireland and Ireland have unique circumstances arising from a UK exit from the EU.

We have been to the fore of Anglo-Irish relationship building for the past 10 years and we know that the strengths and ties run deep between the two countries, not just in terms of trade but as our Prime Minister has said, through “shared history, language and blood ties”.

My own organisation has been lobbying directly with the EU’s chief negotiator, Michel Barnier, emphasising that a hard border serves no one, and we have been making the case that many border communities currently avail of EU funding, which is critical to their accessing health and community services because they are at risk without it.

Neither do we overstate the risks to peace from the consequences of a hard border post-exiting the EU but we don’t trivialise them either, especially in terms of the legacy of the Good Friday Agreement.

All of that said, again there is common ground between the British and Irish governments to do their best to avoid a hard border and its consequences for all involved. The former Irish Taoiseach Bertie Ahern has said the uniqueness of the Anglo-Irish relationship before and particularly after the Good Friday Agreement means that it’s entirely reasonable for both governments to have bi-lateral talks throughout the Brexit process.

As parliament goes into recess and politicians head off for some well-deserved breaks, it’s worth using this time for reflection. The recent Twelfth celebrations in Northern Ireland were incident-free and that was despite the political mood music. This was acknowledged by the Sinn Fein leader, Michelle O’Neill; in recent days a former DUP Minister, Edwin Poots, spoke respectfully of those who love the Irish language and indeed spoke a few words of Irish. These are good omens for the restoration of the devolved Assembly.

I am hopeful, not least because, like the author Alex Steffen, I regard optimism as a political act and I believe that only cynics are those perfectly happy with the status quo and the belief that nothing is going to get better. Looking back at 1997 I have better reason to keep hoping.