“Building the Past”

by Clive Aslet, Editor, Country Life Magazine

This article was originally published in Country Life in April 2009.

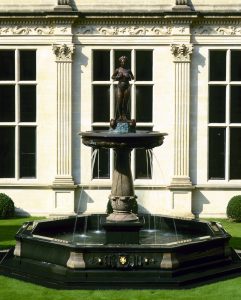

The view from the roof garden of Crosby Hall, near Chelsea Old Church, is one of the most extraordinary in London. There, on the other side of the Tudor courtyard is the Thames, the southern bank lined with recently built, glass-fronted apartment blocks by Norman Foster. Within the quadrangle, a fountain sprays a bronze statue of the goddess Diana with jets of water, in a garden blowing with scented herbs and flowers.

You might think that the scene contrasts the brash, modern city with the stately-calm of a centuries-old palace, but this is Crosby Hall, a mellow, apparently immemorial house, which has not even been finished – after 12 years of building, there are still three more to go. The speed of construction is dictated by the time the specialist craftsmen need to work on their different contributions. Every detail is being executed as closely to carefully researched Tudor precedent as possible.

You might think that the scene contrasts the brash, modern city with the stately-calm of a centuries-old palace, but this is Crosby Hall, a mellow, apparently immemorial house, which has not even been finished – after 12 years of building, there are still three more to go. The speed of construction is dictated by the time the specialist craftsmen need to work on their different contributions. Every detail is being executed as closely to carefully researched Tudor precedent as possible.

Crosby Hall originally stood in the City of London, as part of Crosby Place. It was moved to its present site in 1909-10, when Crosby Place was demolished to make way for a bank. The architect responsible for this work was Walter Godfrey. Writing in the Survey Of London (Volume 4, 1913) he called the hall’s oak roof, divided into eight bays by arched trusses and pendants, “a unique piece of 15th Century design”. In re-erecting the hall, Godfrey was able to repair some features and replace others, using the original Reigate stone. The decayed ashlar on the outside was replaced with Portland stone, presumably because it was better able to withstand London’s polluted air.

In addition, a Tudorish Arts-and-Crafts block was built at right angles to the hall to accommodate the British Federation of University Women, which took a lease on the site. Later in the 20th century, a less satisfactory contribution was made in the form of a concrete and glass structure – so awful that even the otherwise Modernist Pevsner, in his “Buildings of England” fails to mention it – erected on Chelsea Embankment.

With the abolition of the Greater London Council, which inherited the freehold, Christopher Moran was able to buy the whole site in 1988. Mr Moran had the idea of “putting the great hall back into its historical context as part of an appropriate private residence”, designed to showcase the high-status Tudor furniture that he has been collecting since his twenties.

After eight years of negotiation, the planning authorities allowed him to tear down the modern accretions, although not the Godfrey Block, which was listed. This killed any thought that the new Crosby Hall could replicate Crosby Place as it existed in Bishopsgate. Instead, Simon Thurley, now Chief Executive of English Heritage, but then Head of Historical Royal Palaces, devised a different scheme, imagining a building constructed over a century and a half.

The entrance range, inspired by Cardinal Wolsey’s Hampton Court, is Tudor; this gives in to an Elizabethan garden, designed by the Marchioness of Salisbury and centred on the Diana fountain – sculpted by Neil Simmons, it is based on a fountain at Nonsuch Palace, installed by Lord Lumley in the late 16th century (demolished 100 years later). The west range, to the left of the entrance, contains the dining room: externally the giant pilasters, richly carved with ornament, are derived from Kirby Hall in Northamptonshire, a house of the 1570s. (Soon, the Chelsea Embankment will be closed for the delivery of a tree trunk, from which the 45ft dining table – carved from one piece – will be crafted.) The tall Godfrey block has been remodelled to suggest a structure of about 1600.

Every detail of Crosby Hall is vetted, sometimes argued over, by a team of scholars, led by Dr Thurley. He described progress so far in Country Life (October 2, 2008). Then, the exterior of the building was nearing completion, and Charles Normandale’s weather-vane, incorporating a gilded sea stag, already glittered on the turret on the entrance façade. Nevertheless, no interior had yet been completed and the terracotta roundels on the courtyard side – after those containing Giovanni da Maiano’s Roman Emperors at Hampton Court – had yet to receive their portrait busts. That of Thomas More used Mr Moran’s portrait from Holbein’s studio, as the reference. The other heads are those of Mr Moran and his two sons, Charles and Jamie, all modelled by Andrew Sinclair.

Five years later, we are able to show the council Chamber, the first of the state rooms to be finished. If it is a foretaste of what we can expect for the rest of the house, Crosby Hall will be famed as a nonpareil of British craftsmanship; a kind of Tudor equivalent of the Frick Museum in New York. The Council Chamber occupies the centre of the ground floor of Godfrey’s north range, entered directly from the garden.

Externally, the entrance is announced by a grand Corinthian doorcase, carved by Dick Reid. Their lower parts ornamented with strapwork, the columns stand on plinths bearing lions’ heads. Above the entablature, a pair of obelisks stands to either side of Mr Moran’s opulently carved coat of arms. In the spandrels to either side of the door, reclining female Victories hold garlands, as though to crown anyone entering the house. All this is in Bath stone. Carved by Nick Coryndon, the door, a massive oak construction, is itself a masterpiece, the centre piece being ornamented with a head of Medusa in a cartouche. The lock, its keyhole covered by a gilded six-pointed star, has been made by Peter Cartwright, master locksmith of Willenhall and one of the very few craftsmen capable of creating an Elizabethan lock of this complexity from scratch. Shutting the door is as much a pleasure as opening it, because its inner face has been sumptuously inlaid with vases and geometrical motifs. In the centre is the marquetry picture of Crosby Hall.

As you explore the room, made by knocking together “at least 20” of the cubbyhole-like rooms used by the University Women, you find that this is one of a series of astonishing marquetry panels – fauns playing pan pipes, lute players and allegories of music, evoking the musical entertainment with which Mr Moran’s parties often conclude.

Of a piece with the bravura display of the fireplace is the ceiling: an elaborate composition of strapwork and pendant bosses, entirely in white except for the coat of arms in the centre. The floor is laid with a geometrical pattern of coloured Purbeck marble. At one end of the room is the staircase, leading to a gallery and thence to the great hall; the columns of the balustrade echoing those of the upper tier of the fireplace, although here carved in wood.

True to Elizabethan practice, the cornice of the Council Chamber contains a spy hole that enables the master of the house to see who has arrived and time his entrance accordingly. One of the windows on the south wall has received its stained glass, made exactly as it would have been in the 16th century. It frames the view of the courtyard with a delicious piece of architectural trompe l’oeil, inspired by the 16th and 17th century Flemish family of Vredeman de Vries.

Mr Moran eagerly awaits the arrival of the other window, however, he knows there is nothing that can be done to hurry work of this quality, as the specialist craftsmen capable of doing it are rare. The job of finding craftsmen has fallen to David Honour, former head of design at Historical Royal Palaces. His supervision has ensured that the highest standards of historical accuracy have been maintained, every detail having been drawn by Mr Honour full-size in advance of execution. These drawings will be kept at Crosby Hall as part of the archive of the house.

When finished, Crosby Hall will, Mr. Moran hopes, stimulate an appreciation of British decorative arts in the 16th century, an era under represented in the V&A. As Mr Honour comments: “There is nothing here that was not possible for a house of this period.” With all the energy that has gone into researching the details of the house, Crosby Hall is set to become a living architectural resource.

The inclusion of Richard III’s coat of arms in the long gallery is a tribute to the great hall’s Yorkist origin. Already, the long gallery, which runs along the top floor of the Godfrey block, has its ceiling in place; in the fullness of time it will be used to display some of the richest of Mr Moran’s treasures. Mr Moran is thinking of installing his own bed here, “among all my pictures and furniture. I could take breakfast on the roof terrace. Of course, I know it would be historically wrong to have a bed in the long gallery.” Having built so much that is scrupulously accurate, as well as quite wonderful, at Crosby Hall, it is an indulgence that many people would be inclined to allow him.

/ This article was written by Clive Aslet and originally published in Country Life in April 2009.